Fight for voluntary assisted dying laws continues across Australia

The discussion around voluntary euthanasia laws in Australia continues this week, after Tasmania became the latest to reject voluntary assisted dying legislation.

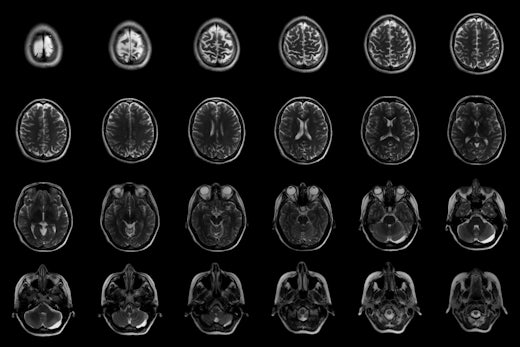

Tasmania recently voted against a voluntary assisted dying bill, making it the third attempt at legalising voluntary assisted dying in the state in 10 years (Source: Shutterstock)

Last week, the Tasmanian Parliament rejected the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2016 in a vote that saw the private member’s bill defeated 16-8.

The bill, which was co-sponsored by Franklin Labor Member of the House of Assembly Lara Giddings and Greens leader Cassy O’Connor, was the third attempt to legalise voluntary assisted dying in the state in 10 years.

The defeat comes only months after South Australia’s push to legalise voluntary assisted dying failed to pass. The matter was put to a casting vote and failed despite support from the South Australian Premier Jay Wetherill and opposition leader Steven Marshall. It has been the 15th attempt to legalise voluntary assisted dying in South Australia.

Despite the defeat, New South Wales is set to be the next state to debate voluntary assisted dying laws, with the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2017 due to be introduced in the upper house later this year. The Bill has been drafted by a parliamentary cross-party working group, made up of members from the Coalition, Labor, the Greens and an Independent, and is currently undergoing a consultation period.

The proposed legislation currently determines that residents will be able to choose to end their own life provided they are terminally ill, over the age of 25 and are likely to die within 12 months. Patients would also need to be experiencing severe pain, suffering or physical incapacity, which would need to be verified by an independent specialist and a primary medical practitioner.

In Victoria, the drafting of a voluntary assisted dying bill has been overseen by a Ministerial Advisory Panel, who this week released an interim report overviewing the consultation process.

The recommendations of the panel are that residents should be legally free to end their own life considering they are over the age of 18, and are suffering a serious and incurable condition that causes enduring and unbearable suffering that is unable to be relieved.

The proposed legislation, which is being directly sponsored by Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews and Victorian Health Minister Jill Hennessy, is due to be presented to parliament following the panel’s final report expected in July.

Shayne Higson, spokesperson for voluntary assisted dying advocacy group Go Gentle Australia, says the failure of Tasmania’s attempt to legalise voluntary euthanasia did not surprise her.

“Based on the proposed legislation in Victoria and the draft consultation bill that’s already been released in New South Wales, it appears that state parliaments in Australia are only going to be comfortable with a narrower assisted dying law,” she says.

“I think it’s important that MPs are fully informed before they face the debate on this important issue.

“Hopefully, with the process in New South Wales and Victoria there will be far more time for MPs to look closely at the details of the bills and seriously consider the safeguards because when they do, I am confident that they will realise all the concerns raised by opponents have been addressed so the vulnerable can be protected.”

When asked if she thought politicians were using their hearts or their heads when forming their positions on this issue, Ms Higson replied that it is “often neither”.

“If they used their hearts, I think they would feel compassion for the people who are suffering every day in Australia in the absence of a law,” she says.

“If they used their heads they would look at the overwhelming evidence and realise these laws can, and do, work safely and effectively. Unfortunately, it is sometimes political expediency that determines the outcome on this issue.”

Chief Executive Officer of Palliative Care South Australia Tracey Watters has over 20 years experience in palliative and hospice care and says the looking to implement voluntary assisted dying laws ignores the legislation already in place regarding to end of life care.

“I don’t think we need voluntary assisted dying laws in Australia, I think we need far more understanding of what palliative care can offer and also far more access for people facing death and bereavement to have specialist palliative care when and where they want it,” Ms Watters says.

“As a doctor or clinician, I need to obtain your consent before I can do anything to you – the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act enables people who are facing their end of life to actually say that they don’t want treatment and that they just want to be made comfortable.

“There are still too many people who receive poor care and inadequate relief, and a change in the law will not correct these deficiencies in care, so until the government invests in palliative care I think they’re taking one step too far in going down the voluntary assisted dying line.”

Ms Watters says that while the proponents of voluntary assisted dying laws argue that most Australians are in favour of such laws, dying people have very different opinions.

“The statistics that are trotted out by the pro-voluntary assisted dying groups seem to show that 80 percent of people surveyed are in favour of voluntary assisted dying, however in my experience I have only ever come across one person who has asked their clinical team to please hurry them up,” Ms Watters says.

“Dying people do feel differently to people who are well and I feel that could be an underlying reason that the bills continue to fail from state to state.”

“The last days can be really important and needed for ultimate peace of mind, not only for the patient but for their survivors, and euthanasia takes that away – we might think we are solving one problem but we are creating another in terms of complicated grief and bereavement.”

![The new Aged Care Act exposure draft is slated for release in December of 2023, but advocates hope to see it rolled out on January 1, 2024. [Source: Shutterstock]](https://agedcareguide-assets.imgix.net/news/articles/wp/agedcareact__0811.jpg?fm=pjpg&w=520&format=auto&q=65)

Comments